Ben Haring, Halah.am on an Ostracon of the early New Kingdom?

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 74, 2 (2015) 189-196.

(July 2018) Other studies of the document are now available to me:

Thomas Schneider, A Double Abecedary? Halah.am and 'Abgad on the TT999 Ostracon.

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 379 (2018) 103-112.

https://ubc.academia.edu/ThomasSchneider

H.-W. Fischer-Elfert, and M. Krebernik, Zu den Buchstabennamen auf dem Halah.am-Ostrakon aus TT 99 (Grab des Sennefri). Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 143 (2016) 169-176.

(November 2018)

Aren M. Wilson-Wright, As Easy as ABC? A Review of Thomas Schneider's Study of the TT99 Ostracon

https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/sites/bibleinterp.arizona.edu/files/2018-10/TT99%20Bible%20and%20Intepretation.pdf

Anticipating the answer to Haring’s question: what we find is a list of words (nouns rather than names, apparently) with the first four having the initials HRH.M; this looks like a failed hypothesis already, but in Egyptian writing there is no L-sign or l-sound available, so r is used for l (though we will need to keep in mind that l could also be transcribed by n, nr, and 3 [’aleph]).

The HLH.M sequence-order for the letters is not known before Hellenistic times in Egypt (4th Century BCE onwards; cp. Schneider 106b) but it is attested in Syria-Palestine in the Bronze Age (before 1200 BCE) and in Arabia in the Iron Age.[1]

Is this an onomasticon (a list of names or words) or an abecedary (an inventory of alphabet letters arranged in a standard order)? If it is an onomasticon, why is it being hailed as the earliest known abecedary? Nevertheless, it could be both, because each word has a symbol after it, and a few of them look like letters (‘pictophonograms’) of the original alphabet. But the total number of such symbols on this fragmentary document is twelve, a long way from the expected double dozen or more; but Haring (195a) surmises that the ostracon was originally twice as long as the surviving fragment; Wilson-Wright also supposes it was a complete HLH.M alphabet; but I will argue that these guesses are unlikely or impossible.

It must be said at this point that none of these scholars mention the oldest complete copies of the early alphabet in its pictorial stage (two inventories on three limestone tablets) which also come from Thebes, and should be cited in any study of the infant alphabet; but, astonishingly and deplorably, they are never consulted (though Émile Puech informs me that he has spoken about them in the past), even though they may provide the solution to all the speculation that goes on in the search for the original letters of the alphabet (by Gordon Hamilton, for example)[2]. However, they have been examined by myself, publicly though not ‘publicationally’, in connection with the theories of Colless and Hamilton.[3]

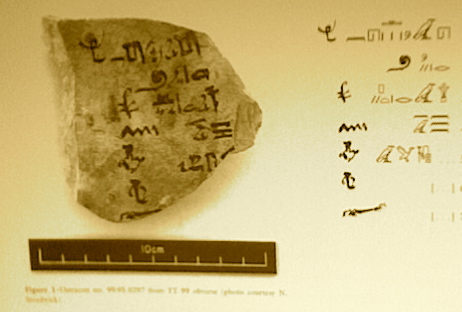

We now begin an examination of this promising artefact. Photographs of each side are reproduced here (after Haring), and for my own use I have produced a paper facsimile of the objecr, by pasting photocopies of the two sides together back to back.

Since Haring (192) gives strong indications that “Group Writing” (Egyptian “syllabic orthography”, a system for transcribing foreign words and names) is present here, we might expect the texts to be Semitic; but he has little success in taking this approach. However, I will presume at the outset (with hindsight) that the words are West Semitic, and that the original pictophonograms that I have proposed for the letters HLH.M (and some others) are there on the tablet.

Haring identifies the sides as obverse (A) and reverse (B), and he notes that the top of A corresponds to the bottom of B; and so the writer must have turned the object over vertically to continue the inscription, rather than simply turning it around horizontally so that the top lines of each text are at the top of each side. The text on A is (apparently) broken off at the bottom, and B possibly (though not probably, if Schneider's interpretation is right) has some details missing at the top. The question remains whether the tablet was originally much larger, containing the entire alphabet, and thus with twice the number of letters (22 or more).

The sign on the left is a hieratic form of Hieroglyph A28, which is believed to be the basis for proto-alphabetic H /h/ and the origin of Greco-Roman E. It represents a man rejoicing, and my long-standing hypothesis (1988: 35-36) connects it acrophonically with West Semitic hll (rejoice, exult, jubilate, celebrate, as in hallelu-yah). The various shapes it has in the Semitic inscriptions also relate it to A32 (man dancing) and even A29 (man standing on his hands).[4]

Haring's transcription of the accompanying text (on the right, and reading from right to left) is h3whn; he supposes this is for Egyptian hy hnw ‘rejoice’, and he sees it as a perfect match with the rejoicing figure. Certainly, but perhaps we can find a Semitic word for this slot. In this regard, Egyptian N (the water-wave sign that gives alphabetic M, pictured further down on this tablet, though reduced to a horizontal straight line in the hieratic script, as shown here immediately to the right of the rejoicer) was also employed to transcribe Semitic l, and so the the two Egyptian letters at the end (HN) could represent hl.[5] Furthermore, the eagle-vulture representing 3 (’aleph) could stand for l (though it would normally be indicating a vowel, here ha or hi. Haring mentions the possibility of another N (and thus an additional l), and I can almost find *hillul, which I see as the word that gave HI in the West Semitic proto-syllabary and H in the proto-alphabet (Colless 1992: 67). Still, the final hl might suffice to make the confirmatory connection that I have been waiting for, since 1988. Haring follows the standard line that the name of the letter is Hoy (or Hey, presumed to be what the man is shouting) and Hoy happens to be the Ethiopic name of the equivalent letter. Another Ethiopic letter name will be invoked in the next section. Notice in passing that the H-sign (hieroglyph O4, a field house) was one of the models for the letter B (bayt ‘house’; Hamilton 2006: 38-52); indeed, it was the one that survived into the Phoenician alphabet.

Schneider thinks that a connection with Hebrew hll "praise", as proposed by Fischer-Elfert and Krebernik (2016:170), is unlikely, in the unattested form hlhl that appears here (apparently); instead he suggests a Semitic root hny "be pleasant", and here with causative ha- ("make pleasant"); I would still cling to the hll "exult" connection (hillulu "jubilation"), as the original reference for the character depicted to represent H /h/; and whatever the scribe has intended here, he has certainly written a term beginning with h (hieroglyph O4).

We should keep in mind and test the supposition that each Egyptian syllabic transcription covers a Semitic word, whereas the classifiers are Egyptian.

Accordingly, I think the symbol of the man rejoicing is meant to give us the sound of the first consonant in the series, perhaps by means of the Egyptian hy hnw "jubilate" (Gardiner, 493, with reference to A32 man dancing), though A8, with the man sitting, is even better, as it represents hnw "jubilation".

An interesting detail must be added here: I am convinced that in some, if not all cases, the document does in fact provide the Semitic alphabet sign. In this instance I detect a faint representation of the letter H (man with upraised arms at right angles) in the space below the Egyptian hieratic H.

[A2] L

Haring transcribes the text as rw (rawi) and looks for a word to go with the “curl or rope at the end”. Actually, it is a already a current idea that the original letter L was a ‘coil of rope’, corresponding to hieroglyph V1 (Hamilton 2006: 126-127). Also, Egyptian r was used to render Semitic l (more usually than n for l, as proposed in A1 above); remember that there was no l-sound in Egyptian. If we are looking for a word lawi, we can find it in the Ethiopic name for L, Lawi. Romain Butin noted this (Harvard Theological Review 1932: 146, and also Colless, Abr-Nahrain 1988: 44), and Butin pointed to a root lawa ‘wind, coil’ (as in Arabic); Hamilton records this in a footnote (2006: 136, n. 157) but he rejects the other possibility of a shepherd’s crook (S38, S39) as the prototype (2006: n. 148). However, on the two alphabets from Thebes, neither L has a coil: one has a crook (like S38) and the other has an inverted example of S39 (looking just like our l). It could be that they are allographs: either the coil and the crook are both original, or else one developed from the other. Note that the other four scholars (Sch, F-E, K, W-W) also invoke the root lwy here. In this case, we again have a transcribed Semitic word; and the glyph V1 presumably has its usual Egyptian function as a determinative for rope, though it does not have a phonetic role.

[A3] H.

Here the text is transcribed as h.rpt (note that when I place a dot after a letter it should be understood as actually being beneath the letter, in accordance with the standard transcription system for h., s., z., t., d.) The H. sign is M16 (clump of papyrus) used in Group Writing instead of the normal V28 (hank or wick), which became H in the proto-alphabet. Haring offers a proper name h.rpt in Ugaritic cuneiform sources, but he wonders how this and his other suggestions would relate to the sign on the left. He identifies it as “M22” (“a reed plant”) but the sign has two shoots on each side, whereas M22 has single shoots, and so this is M23 or M26 (sedge). If we search for Semitic h.lpt we discover h.lp, as a species of rush with sharp edges (root h.lp ‘be sharp, cut’) (Marcus Jastrow, Dictionary of Talmud etc, 456f) and ‘shoot’ (plural –ym or –wt) (Jastrow, 472a); it is cognate with Arabic h.alaf or h.alfa’, and it is especially found in Egypt; it is glossed as ‘Schilf oder Riedgras’ (Jacob Levy, Wörterbuch über die Talmudim und Midraschim, II, 63a). ‘Schilf’ is ‘sedge’ (Germanic sagjaz; sag-‘saw’). I have now learned that Schneider, Fischer-Elfert & Krebernik, and Wilson-Wright also read h.lpt "rush, reed", and connect it with Semitic h.lp (also Akkadian elpetu)].

The sedge sign that comes at the end of the h.lpt sequence is not in any proto-alphabetic text that I have seen, though M22 with single shoots does occur in the West Semitic syllabary, apparently as mu, from mulku, ‘kingship’, after M23 nsyt, ‘kingship’ (Colless, Abr-Nahrain 1992: 82-83). Additionally (smudged and faded, and unmentioned by the other researchers), the Egyptian mansion-sign (06, h.wt) is placed here to reinforce the fact that the third letter in the series is H. (Het in Hebrew). Note that the Ethiopic name for this letter is H.awt., and this may be significant. The sedge might have served as an allograph for H. in the proto-alphabet, but my choice has always been the mansion sign for H., acrophonically based on h.z.r (Hebrew h.as.er) ‘court, mansion’ (Colless 1988:38-41). Its form in the alphabet in the Iron Age is an upright rectangle, divided into two squares; in the Bronze Age, the earliest form has the mansion with two rooms and a courtyard (sometimes rounded), but because it is a house it is usually, but mistakenly, placed in the B (bayt, house) category (so Hamilton 2006: 48). This character apparently occurs here, to the left of the h.wt hieroglyph and the rush sign, as faint lines and dots. I have waited a long time for such confirmation, while others have been misidentifying H.et as a fence (Hamilton 2006: 97-102).

Also in the vicinity is a small circle with a dot, apparently the head of a snake, with its body represented by a line extending to the wavy line (M); the snake is the letter N in the alphabet, and in the Alpha-Beta order of the letters the sequence LMN is at the half-way point, but in this Ha-La-H.a-Ma system only N is at the centre of the line; but this scribe is perhaps reminding us that M and N really belong together, implying that he knew the alternative order. Or we are seeing MN, another transcription of the word for water (see notes on line A4).

Note that at least 18 of the 22 letters in the Iron Age (Phoenician) alphabet had a counterpart in the ancient syllabary (which likewise represented only 22 consonants); but this form of H. (mansion) is absent from the syllabary. It appears quite clearly in the top left corner of Thebes alphabet 1, and in the same position on Thebes 2 (but indistinct). Those documents portray a longer alphabet, it needs to be said, and it will be necessary to ask whether this little tablet is presenting a long or a short consonantary.

[A4] M

Here the text is transcribed mw n3. The first character consists of three parallel lines (actually wavy lines in the hieroglyph, M33b, “three ripples”, mw, ‘water’). The single “ripple” is Egyptian N (from nt ‘water’), and in the West Semitic syllabary it functions as mu (an allograph of the rush sign for mu, as seen in section [A3] above); in the proto-alphabet it is M, and now only two of its waves remain (Colless 1988: 44-45; Hamilton 2006: 138-144). The proto-alphabetic sign, here with four waves, could indicate that a word starting with m precedes it, or even the word from which M originates, possibly mûna (the plural ending n, as in Arabic and Aramaic, whereas Hebrew, for example, has m; cp. Arabic -ûna versus Ugaritic -ûma). Significantly, Wilson Wright transcribes the word here as mawūna. In my reading of the Sinai proto-alphabetic inscriptions, both -n and -m are attested (nunation and mimation): ns.bn "prefects" (Sinai 349), s.btm "handfuls" (Sinai 375). In this case the symbol has to be interpreted as the West Semitic letter of the proto-alphabet (M), not Egyptian N; the serpent is there perhaps to remind the reader that the Semitic letter N is the snake, or to provide another transcription of the word for water (mn).

I am reasonably convinced that the HLH.M sequence is present in A1-A4. But where does it go from here? In the attested examples of this order (from Syria-Palestine and Arabia) the next letter should be Q, as recognized by Haring (193b, though Haring’s Table 1 erroneously shows O); Q is followed by W, and then Sh and R.

The text in this fifth line is damaged, and Haring's transcription is r/t/d ssh p3. The second sign is understood by Haring as scribal apparatus (Y3), including a palette. The West Semitic word r-sh-p refers to ‘plague’ or the god of pestilence, or ‘burning’. The accompanying object looks like a pot with a handle and a spout; it could be for pouring libations. By my reckoning the letter Q was originally a cord wound on a stick (qaw, a line, a cord used for measuring) sometimes with one end of the cord projecting at the top (Colless 1988: 49-50, Sinai 345, Sinai 376); this is widely attested in the inscriptions, and on both copies of the alphabet from Thebes, but Hamilton overlooks this and argues for Qop as a monkey, using the letter that is actually Sadey for his false guide in the chase (2006: 209-221). This is not an ape that is confronting us at this point on this tablet, but it could be a human head, inverted, with ears and neck. The name of the letter R is Rosh, ‘head’, and rssh might be a transcription of that. Rather than hieroglyph D1 (head in profile) this would be D2 (front view of head with neck and ears and eyes, h.r ‘face’). However, the initial R of the text is not certain, and the final –p3 is left unexplained.

The symbol could even be F34 heart (Egn ’ib, WS lbb), and this would lead to a whole new round of speculation.

Wilson-Wright has li-qôpi ('to the monkey'), but the supposed r q p 3 is explained by Schneider as Semitic qab (a measure, with the vessel symbol as "classifier") preceded by the preposition l, so that the Q is the acrophonic agent in the sequence. However, ultimately we must accept that the accompanying symbol is a perfect match with hieroglyph W23 (jar with handles, Gardiner, 530), which is associated with an Egyptian word qrh.t "vessel", and conveniently and fittingly provides the sound Q. With regard to the accompanying word, West Semitic has qb`(t) "drinking vessel", but this has more sounds than allowed by the text on the stone. The monkey wins on two counts: rqp is Semitic lqp, 'for the ape', and the animal is pictured, apparently.

Incidentally, the intrusive preposition could indicate that a statement is being made, or a story is being told, by the Semitic words in the sequence (Schneider).

[A6] W

The text to accompany this sixth sign is lacking; possibly a piece of the stone has been broken off at this point; or else the scribe thought that A6 and A7 were self-explanatory. Haring suggests, plausibly, that the glyph is a seated man with arms hanging (hieroglyph A7, wrd ‘tired’) but he does not pursue this possibility. I have seen this in association with an early alphabetic inscription from Timna in the Wadi Arabah (Colless 2010; Timna iscriptions) and I took it to be an ideogram there. Notice that the word wrd ("wearied"!) begins with the expected W in the series. Also, to the right of the weary man, is that a pair of lollypops, circles on stems, the sign for W, with WW saying waw ('nail'), and giving the name of the letter?

[A7] Sh

The Beth-Shemesh HLH.M sequence of cuneiform letters has a circle after W, and this is followed by R; this circle would represent the sun, which is the acrophonic source of the Sh-sign, sh-m-sh "sun", although this fact is almost universally unrecognized. The original character was the sun disc with a serpent (appearing in the Timna iscriptions, and twice on the Wadi el-Hol vertical inscription, though not perceived as such by other researchers; see Hamilton 327-330). Symbol A7 here could be an elongated version of the sun-hieroglyph. The example from Ugarit (RS 88.215) has (apparently) Th (T), but both documents (from Beth-Shemesh and Ugarit) are damaged. The circle-character usually indicates a short cuneiform alphabet. No text is available on the tablet for this last sign on side A. Haring proposes a phallus or an animal. If it is a letter of the alphabet it could be a human arm (yad) with the hand pointing downwards (hieroglyph D41, determinative for arm), and hence Y. Incidentally, the Ethiopic name for Yod is Yaman ("right hand"); this word was the source of YI (yimnu) in the West Semitic syllabary. The next expected letter in the sequence would be Sh or Th, but Y is actually the final letter in the series (as attested at Ugarit, and apparently also Beth-Shemesh, but not in the Arabian and Ethiopian system); this may be significant, indicating that the scribe only intended to give an abbreviated list. This could mean that the other side of the tablet has a different purpose, and Schneider suggests that it represents the 'ABGD form of the alphabet. Schneider's hypothesis has merit, since the words in B2-B4 have initial B G D.

However, once again the faint marks can settle the matter: to the right of the W (wearied man) we can discern a sun-sign, and thus Sh (from shimsh, "sun"); referring to the original photographs in JNES and BASOR, rather than the blurred reproductions offered here, we see on the far right a circle, representing the head of a protective serpent, with its body to the left (like a curved W), and the sun-disc is included, apparently; or there may be a snake-head at each end.

We now turn the tablet over to side B, presumably the reverse side. Haring assumes this to be the final half of the end of the inscription, and he posits six items.

[B0]

This is “lost except for some traces” (Haring); or else there was never anything there. I think that the first line of the reverse side is B1.

The tentative transcription is t/r/d/n.w-t3…(?); the final cluster of three marks is left undeciphered. Wilson-Wright offers rnttwj, and suggests daltu 'door', hence D. Haring’s guess is the name of the cobra goddess Rnn.t.

However, 'Aleph (the glottal stop) would be expected, preceding B (which is certainly the next letter in the present sequence), and Schneider comes up with a reading that at least has a word starting with a (prothetic) vowel, but transcribed without an initial glottal stop: (')elta'at "gecko". If the marker is indeed a lizard, then Hebrew 'anaqa provides an 'Aleph (listed with Schneider's word among prohibited reptiles in Leviticus 11:30); but it would be hard to find that sequence of sounds in the text. The remains of the Egyptian symbol could be the tail and rear legs of the lizard hieroglyph (I1, `sh 'lizard'; the initial consonant is used to transcribe Semitic `ayin, but is sometimes employed for Semitic 'alep, and that could be the case here.

With that in mind, I would now like to direct our attention to the horned bovine head at the far left of this line, faded but clear enough on good photographs; this is the original pictophone that became 'alep and Alpha. Thus we are left in no doubt that the intention is to present a sequence starting with the letter which stands for the glottal stop; and we would confidently expect the next sign to be Beta.

Two ibises and two reed flowers, and a few more undecipherable marks, give us bby… . The symbol looks like a (four-legged) beetle or a bee. If it were an ox-head with a neck (like the one on Thebes 2, or ’A in the syllabic texts from Byblos) and if there were two Egyptian vultures (G1 3, ‘aleph) instead of ibises, then 33 could represent ’l, but there is no p or b to produce ’lp. Still there are marks preceding the ibises, which could be the true initial letter. If 3 for Aleph were to fill the gap, we would have ’bb, ‘green ear of corn’, or the month of Abib, to go with the sedge shoots in [A3] above, and we begin to wonder whether this could be a calendar of some kind, with twelve months itemized. But Schneider offers Egyptian bibiya-ta' "earth-snail"as the solution, with the beetle as a classifier; he also adduces Berber baybu "snail". If it is a scarab-beetle (L1), it would be phonetically kh-p-r, but as a bee (an anomalous L2) it offers bit, with the desired B. If this were a long alphabet, the order would run 'A B G Kh(H) D; but we seem to be at the B-line of the sequence at this point (after all, the operative Semitic word starts with double b), and with hindsight I can find no place for H in this collection; this would indicate a short alphabet.

Wilson-Wright proposes bi-bayti, 'in a house', which has the merit of giving the actual Semitic word that produces the letter B (baytu "house"). Again, the insertion of a preposition suggests a meaningful series: "There is a lizard in the house".

[B3] G

The first letter of the text is the Egyptian G (W11, a ring-stand for pots, nst ‘seat’); it can transcribe Semitic g, q, k, gh. Haring’s transcription is gr(y), for which he proposes ‘bird’, and the accompanying symbol is apparently a bird in flight, though he tentatively identifies it as hieroglyph G47 "duckling", phonetic t. Schneider decides on Egn garu "dove", and points out a connection with columba. Wilson-Wright suggests gallu as a reduction of gamlu 'throw-stick', which is the origin of the letter G. Are the lines to the left of the B2 symbol (and below the ox-head) depicting a boomerang? The intended word should be Semitic, but at least we can say it starts with G.

[B4] D

Haring gives t3’ity(?) and makes numerous suggestions for the symbol (sarcophagus, shrine, temple door, vertical loom) and for the word (temple door, Tait the goddess of weaving, bale of linen, loincloth, curtain). Wilson-Wright seeks the letter T.et here, proposing a vertical loom for the depicted object, and transcribing the syllabic text as t.aytu. The letter D is undoubtedly derived acrophonically from dalt "door". The symbol reminds me of the grapevine structure (cp. M42) which is the letter Gh(ayin) from ghinab, ‘grape’. But it is very close to hieroglyph O20, depicting a shrine. Schneider suggests it is a bird cage, and he identifies the word as da'at "kite" (Leviticus 11:14). But could the transcription represent dalt ('alep = l), with the marker representing an elaborate door (Haring's "temple door")? Is there a simple door for D (with thick lines) to its left?

[B5] Z

The transcription dr “seems inescapable”, Haring says, and the symbol appears to be a vessel. It certainly looks like a pot, but it could be a bag, which is the sign used for S. (Sadey). The D is a fire-drill (U28), and d is also used for Semitic s. (Sadey). My long-held acrophonic source for S. is s.rr, ‘tied bag’ (Colless 1988: 48-49). Am I having yet another Eureka experience here? However, the preference is for Z here, invoking zir "jar" (though the Hebrew word is sir, and Arabic zir is late, though in an addendum, F/K note Akkadian zurru, attested at Mari and Alalakh). The original Letter Z is attested as |><|, and such a combination of triangles might be found to the left of the B4 line.

As is ever the case, only the person who composed this text knew for certain what it means.

What could the significance of this document be? Was it apotropaic, using Semitic signs and spells and names of goddesses, to ward off evil in the tomb? The West Semitic serpent spells in Egyptian royal tomb inscriptions (5th Dynasty) might offer an analogy here, but I can not see a clear connection (Richard C. Steiner, Early Northwest Semitic Serpent Spells in the Pyramid Texts, Winona Lake, 2011).

It now appears that this tablet is a mnemonic guide to the two standard systems for arranging the letters of the alphabet: the HLH.M and the 'ABGD schemes.

The single-symbol "classifiers" (Schneider, 104) seem to be semantic and phonetic indicators. In some cases we see hieroglyphs corresponding to the West Semitic letters: A1 H, A2 L, A3 H., A4 M, A7 Sh, B4 a door?.

Additionally, actual letters of the Semitic proto-alphabet appear in relevant places: mansion (A3, H.et), monkey (A5, Qop), sun with uraeus serpent (A7, Shimsh, Shin), ox-head (B1, 'Alep), house (B2 Bayt), throwstick (B3, Gaml) are examples that I alone have identified, but I think they are there, and they add significantly to our understanding. Indeed, there are so many traces of proto-alphabetic letters on the far left area of each face of the tablet that it almost seems to be a palimpsest.

Connections with the names of Ethiopic letters seemed promising at the outset, but no consistent pattern has been found.

Apparently the aim was to give examples of the sounds represented in the West Semitic proto-alphabet, by means of the initial sounds of a set of words (preferably Semitic) arranged in the two standard orderings of the letters The words were possibly chosen to hang together in a pattern for memorisation purposes. The existence of such a tool was known from a later period in Egypt (Merkvers, Schneider 106b - 107a)

Perhaps we can find a mnemonic ditty.

(A) (1) Rejoice, (2) bender of (3) reeds, (4) water (5) in jar for (6) the weary (7) from sun.

(B) (1) Lizard, (2) snail (or in the house), (3) pigeon, (4) kite, (5) in the pot.

However, more opinions are needed on the right readings for the hieratic texts and symbols in the inscription; and other suggestions for the purpose and purport of this intriguing artefact. Wilson-Wright has provided some promising new readings (2018, see below).

This is not a complete document, though it may be a copy of the beginnings of two standard texts. However, the tablet itself is complete (or almost complete and possibly unbroken). There was no space for more writing on either side, and since the two texts are running in different directions (the top of side A is the bottom of side B), it can not easily be argued that this is a fragment of a larger broken tablet.

Side A is the obverse; and side B is obviously the reverse side, since it omits H and W from the 'ABGDHWZ sequence, as they had already appeared on "the front page".

Side B has the shorter form of the alphabet, as shown by its omission of H between G and D.

Side A does not go far enough for us to determine whether its alphabet is long or short; HLH.M alphabets are usually long (South Arabia, Ugarit), but if A7 is the sun, and thus Sh, then this would indicate a short alphabet or a variant version; in the cuneiform alphabets known to us at present, Beth-Shemesh has a circle for the sun-disc [Shimsh]; the Ugarit tablet has a breast with nipple [Thad]; but both these tablets are damaged, and so the evidence is unclear.

Note that the two inventories of the letters of the alphabet from Thebes have no detectable scheme for organizing the signs; they differ from each other in their arrangement; but neither of the two systems portrayed on this tablet are evident there.

This is an important document, and although there are still some puzzles left for us to solve, Thomas Schneider has shown what it is: a double abecedary, albeit abridged. From my experience, I would say that the Alpha-Beta side gives the beginning of a short alphabet, since the H is absent, between G and D; and if the Ha-La side has Sh (a sun-sign with uraeus, equivalent to the sun-disk circle on the Beth-Shemesh cuneiform tablet) after Q and W, then it would also be a short inventory or a variant version, as the long version from Ugarit has Th (from thad 'breast') in this position (Albright's thann "composite bow" for t is highly suspect, but must be mentioned here). The H and W are omitted between D and Z , presumably because they have already appeared on the other side, and this would indicate that the Ha-La face is the obverse, with the 'A-Ba list on the reverse.

han-represents a form of the Semitic definite article attached to the following word.

[with snake for mwn, nunation instead of mimation]

H L H. M Q W Sh/Th R B T (D) K N H S. S´ P ’ ‘ D./Z. G D Gh T. Z (D) Y

Where is the Y in the sequence on the reverse side of the TT99 tablet? There is no space for it (remember that the bottom of the verso is in the same position as the top of the recto, the front side). I could salvage his hypothesis by pointing to the possibility of a Yod at the bottom of the front side (unless it is Sh). However, there is less need for special pleading if we defend Schneider's 'BGD hypothesis for the reverse side.

Deficiencies in Wilson-Wright's case could be:

No known HLH.M system ends with D B G T. Z

The faint icons (for 'A, H., N with M, monkey with Q, sun-icon for Sh) are not taken into account.

The last two signs on the front side (6 W, 7 Sh) are disregarded.

The question of long and short alphabets is not broached.

Erroneously connects fish and door as allographs of D (p. 9, after Hamilton, 61-63).

Somebody had to try that approach, but it does not seem to work satisfactorily.

The tablet is apparently complete, giving a mnemonic arrangement of the first few letters of the proto-alphabet in the two standard sequences: the HLH.M order on the obverse, and the 'ABGD (short version without H between G and D) on the reverse.

My summation of the contents of the document (setting aside the mnemonic aspect, and the identification of the Semitic words transcribed in Egyptian script) would be:

Front: H (h) L (r) H. (h.) M (m) Q (q) W (w) Sh (sh, sun-icon)

Back: 'A (bovine head) B (b) G (g) D (d) Z (d)

(Note again that when I place a dot after a letter it should be understood as

actually being beneath the letter, in accordance with the standard

transcription system for h., s., z., t. .)

In reply to Wilson-Wright's criticism that the Z in fifth position "does not conform to the abgad order": the scribe has skipped over H and W on side 2 because they have already been played in another suite on side 1 of the recording.

Similarly, the missing H between G and D might be explained as an indication that the scribe did not distinguish H and H. and considered that this sound had already been recorded on the HLH.M side of the tablet; or H had simply dropped out of the longer consonantary (the Protoconsonantary) and the shorter version (the Neoconsonantary) was being exhibited.

http://cryptcracker.blogspot.co.nz/2014/09/goldwasser-alphabet.html

COLLESS, Brian E., "Recent Discoveries Illuminating the Origin of the Alphabet", Abr-Nahrain, 26 (1988), pp. 30-67. A preliminary attempt to construct a table of signs and values for the proto-alphabet, and to make sense of some of the inscriptions from Sinai and Canaan.

COLLESS, B.E., "The Proto-alphabetic Inscriptions of Sinai", Abr-Nahrain, 28 (1990), pp. 1-52. An interpretation of 44 inscriptions from the turquoise-mining region of Sinai.

COLLESS, B.E., "The Proto-alphabetic Inscriptions of Canaan", Abr-Nahrain, 29 (1991), pp. 18-66.

An interpretation of 30 brief inscriptions from Late-Bronze-Age Palestine.

COLLESS, B.E., 1992, "The Byblos Syllabary and the Proto-alphabet", Abr-Nahrain 30 (1992), 15-62.

COLLESS, B.E., 1996, "The Egyptian and Mesopotamian Contributions to the Origins of the Alphabet", in Cultural Interaction in the Ancient Near East, ed. Guy Bunnens, Abr-Nahrain Supplement Series 5 (Louvain) 67-76.

And my other articles on the Canaanite syllabary ("Byblos pseudo-hieroglyphic script") in Abr-Nahrain (now Ancient Near Eastern Studies) from 1993 to 1998, culminating in:

COLLESS, Brian E., "The Canaanite Syllabary", Abr-Nahrain 35 (1998) 28-46.

The following two paragraphs from my first draft are now obsolete.

{Another possibility springs to mind, with inversion once again (as for A5 above). Could this be hieroglyph M16, “clump of papyrus” which was used in a hieratic form for h. at the start of section A3 above? Hamilton (2006: 196-209) invokes this as his origin for Sadey, after having employed the true S. character for Q (relating it to its Hebrew name Qof "monkey"; in his note 254 he labels my choice of V33, a tied bag, as “bizarre”). In the present connection, Hamilton (200, Fig. 2.61) provides drawings of early hieratic versions of M15 (“clump of papyrus with buds bent down’) which match the character here before us (without inverting it) and compares them with South Arabian forms of S.; this is a very attractive idea.}

{ My very tentative suggestion is that we have an inverted K here, and it stems from the identification I make for the three-branched character which is taken to be S. by others, but in my scheme as syllabic KI and alphabetic K, and it would derive from kippa ‘palm branch’, alongside a hand sign for KA and an alternative K, from kap ‘palm of hand’ (Colless 1988: 43-44, modified in 1992: 78-79). However, this character could simply be a hand sign with only three digits shown (the example on Thebes 1 is like this, but it could be either animal or vegetable), but the bent middle figure is puzzling. Yet again the writer’s intentions are not yet clear to us.}